Abstract Art: the Personal

Hidden in the Impersonal

The most pathetic error of an art critic is not that he is wrong or that he fails to understand, but that he understands a work of art for which he has no true feeling.

- Ramon Gaya

The aim of this piece is to explore the question of how to respond to, or evaluate, abstract paintings.

Starting point

Talking to the Berrara artist, Robert Simpson, and looking at his abstract works gave me a realisation. Abstract art is more personal than figurative art. It means something to the artist who created it because the image appeals to them in some way, but the viewer does not have this personal relationship to the work. The viewer comes in "cold" and lacks any handle to grasp. To have a good appreciation of the artwork the viewer needs to have some idea of what the artist was trying to do. A totally abstract work of art provides little clue as to what the artist was thinking. It does not make it easy for us to know what its meaning was for its creator. By contrast, representational art deals in familiar shapes, which evoke familiar responses in each viewer.

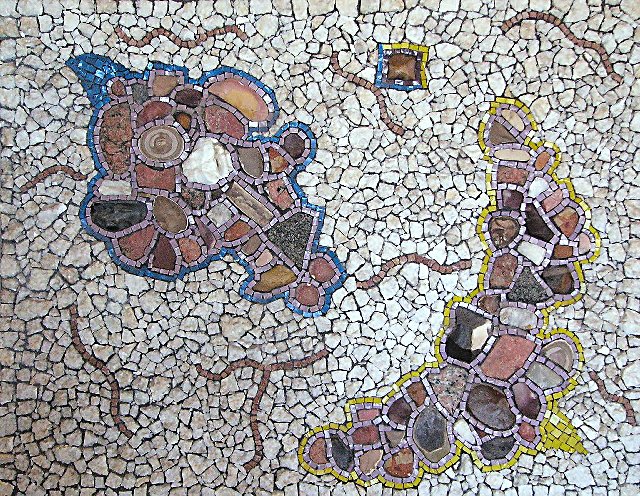

Abstract mosaic by Tad Boniecki

Doodling as art

I saw this personal aspect in my own abstract mosaic. (Award yourself zero points if you asked “What is it?” as you looked at the above image.) I liked the form I was creating, it came from me and so it was "mine" and hence appealing to me, but there is no reason why it should appeal to others. I like to doodle and I may even like the results, but I don't expect other people to appreciate my doodles. I find that I prefer to make abstract works than to look at other peoples' abstractions. It is much like telling people your dreams - other people are generally not much interested because they are your dreams, not theirs. It is natural to like what we ourselves happen to think up simply because we thought of it. This contains an element of narcissism. (Note that it is a standard trick of persuasion to pretend that the person you are trying to persuade originated the idea you are proposing.) I suggest that this narcissistic element is more prominent in abstract art than in figurative art. I find it hard to avoid the suspicion that many an abstract artist is a glorified doodler.

Poetic licence

The abstract artwork is more personal because the artist has more choice, being totally unconstrained by the subject of their piece (if it has a "subject" at all). There are no rules or conventions to follow when creating an abstract work, no need to make it resemble anything in particular. This complete freedom allows its creator to give full play to their personal propensities or predilections. The artist can be as idiosyncratic and self-indulgent as they wish, since there are no rules. It is as though a writer could abandon all grammar, punctuation and semantics, being able to just put down words or letters as the mood struck them, with no constraint of intelligibility.

Transforming the familiar

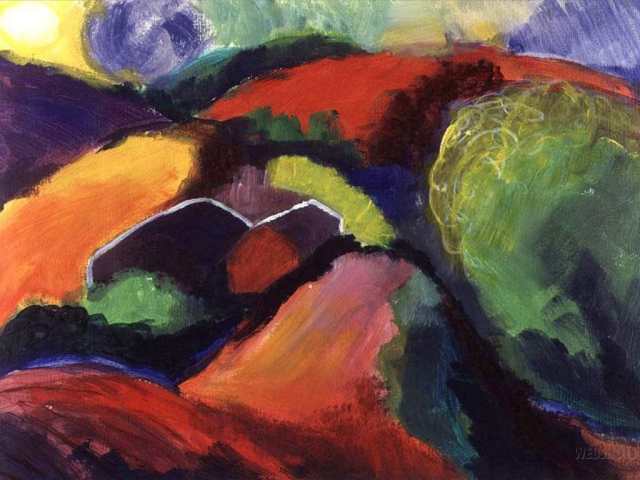

If the abstract artist is painting a scene then they interpret it in a way that amounts to a radical transformation of the visible forms into the shapes that they put onto the canvas. This is highly personal because another artist would probably do it entirely differently, ie they would abstract out different aspects of the scene and transform them according to their own private method, using their own personal visual vocabulary. The painting below recalls a landscape and may be based on an actual scene. Yet if another artist were to paint it the result would probably be unrecognisably different – with different colours, shapes, degree of abstraction and so on.

“Land” by Jenifer Wates

The nature of abstraction

One artist observed that abstraction is the underlying structure of any painting. She justified this by saying that any subject can be broken down into simple lines and shapes. This brings us back to the definition of abstraction - the isolation of the basic elements of a particular thing. Yet the connotation that is most often linked with abstraction is difficulty. Abstract thought, such as is used in mathematics and philosophy, does not come naturally to most of us. It represents a greater level of difficulty than does concrete thought. So it is no wonder that abstract art is difficult for most people. In particular, the process of abstracting out visible forms is not one that many people are familiar with, unless they have themselves painted an abstract based on an actual scene.

There are two different, though related definitions of “abstract”. The first refers to art that does not contain any recognisable forms (eg the painting above). The alternative definition states that abstract art does not aim to depict or imitate anything in the real world. It does not “abstract out” elements of a subject, but has no subject at all, at least not in the sense of a subject that is part of the visible universe. For instance, the abstract expressionist art movement (see the two Pollock canvases further down) sought to express feelings by means of spontaneous “action paintings” that were meant to tap into unconscious sources of creativity. To what degree they managed to impart feelings to their (usually huge) canvases is a major open question.

Inching towards oblivion

People want to relate to an artwork, to connect with it somehow. If there is nothing recognisable in it then that process is made much harder. Many people have learnt to appreciate non-figurative art, yet most of these people still prefer semi-abstract to pure abstract works. I certainly do. There is a sliding scale from semi-abstract, to nearly abstract, to fully abstract art, in which there are no identifiable forms. The artists Klee, Miro and Dali occupy various points in this continuum, somewhat short of full abstraction. Their works are hard to digest for people who are not used to "modern" art. As I became used to their paintings these artists have become increasingly accessible to me. So a learning process takes place: one can learn to appreciate increasingly abstract works. Yet I have not reached the point of being able to appreciate purely abstract canvases (except as decorations). The Miro below is a little short of full abstraction, having some forms that are familiar, such as stars, faces and moon. Award yourself a point if you can see the dragonfly.

“Dragonfly with Red Wing Tips”

by Joan Miro

Retreat from creativity

Abstract art is less creative. A creative product has two dimensions: newness and construction. The first is present to a large degree in abstract art, but the second element is mostly lacking because there is usually no apparent structure or pattern (or else the pattern is so repetitive or so simple as to be without interest). That is why semi-abstract art is more likeable – there is much more for the eye to respond to. Semi-abstract art has freedom but with some constraints, in the form of recognisable shapes that guide our response. However crazy a cubist, fauvist or surrealist canvas may be, it gives us something to react to. It elicits a response, whereas an abstract work mostly does not. It simply does not connect. By contrast, the semi-abstract Dali canvas shown below offers something to ponder on.

Abstract art is less creative than traditional art in much the same way that photography is less creative than painting. Taking a photo is less creative than painting because all that's needed is to press the shutter release. The object or scene is already there, ready-made. Only a good eye and the technique to capture the subject are needed. Likewise, most abstract painting consists of very little by way of construction (though there are some exceptions). On the other hand, a traditional artist starts with a blank canvas and needs to carefully build up a complex image from scratch. By contrast, the abstract artist can just daub a blotch of paint onto the canvas and the masterwork is already finished.

Another way to put it is that creativity involves both art and craft, ie the imaginative and the constructive dimensions. Photography and most abstract paintings fall short on the craft ie the constructive aspect. At the other end of the spectrum are what I call 'craft' paintings - realistic oil pictures that show no imagination but just the routine application of painting technique to the portrayal of a scene. These too are deficient in creativity, but for the opposite reason to the abstract ones.

“The Persistence of Memory” by

Salvador Dali

A truly modern art

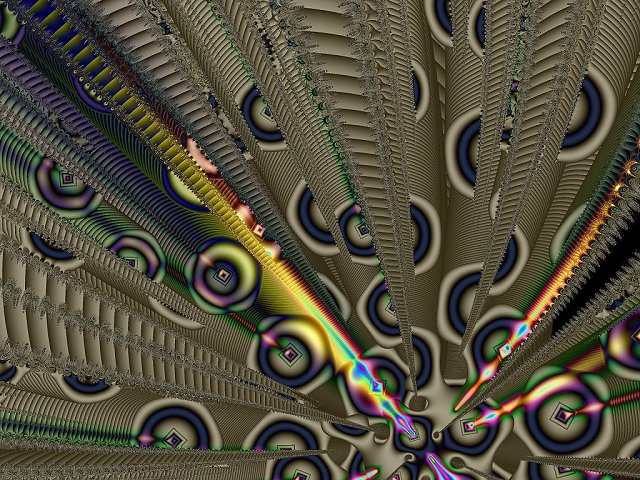

While abstraction is not new and is approaching its 100th birthday, recently, a new form of art has been created - computer art. One branch of computer art are fractals. A fractal is a kind of graphic generated by a computer calculating an equation. I find fractals fascinating because they demonstrate intriguing and complex structures and patterns. In truth, they are abstractions since they do not depict anything in the visible world. Many of these rich patterns do not resemble anything we know. Although in many cases a fractal does resemble something in real life, that is not the key to why I like it. Fractals are a window onto an alien world where mathematics and esthetics intersect. To me a fractal is good if it is beautiful, or if it is intriguing, striking or powerful. Perhaps abstract artworks can be evaluated in much the same way to fractals. The fractal below does not show any recognisable forms, yet it has structure, movement and even perspective.

“Tiera4172 Alien generator” by Tad Boniecki

Another 20th century art form

Another form of modern art is photography. I have taken a number of photographs of water running over pebbles and rocks. These images are almost abstract in that they contain hardly any recognisable forms, apart from bubbles, shells and ripples. Paradoxically, however, they contain or appear to contain, hidden images. The more I look at some of these photographs, the more I can identify small faces, figures and animals in them. I managed to find 28 hidden images in one of my photos. These hidden images are partially subjective and partially objective, in that some people can "see" a particular image, whereas others do not (even when it is laboriously described to them). They may see something else instead. Yet to me the esthetic value of one of these photographs does not depend on finding any identifiable forms. Either the image as a whole makes a visual impact and has esthetic appeal, or it doesn't. (Award yourself a point if you can see a shell below.)

I like to take abstract or semi-abstract photos for a number of reasons. There is the childish pleasure of confounding the viewer, challenging them to work out what is depicted. There is an element of play, of playing with the visual environment, as with paints or collage. Just the materials are different. Then there is the element of discovery, of seeing the familiar anew. There is the simple delight in pattern itself, pattern divorced from subject matter. A particular configuration appeals to me or intrigues me. I like it for its own sake, not because it is an image of X, nor because it reminds me of Y. Then there is the joy of creating a form never seen before, preferably with some complexity.

At times we look at something but cannot tell what it is, whether because we only see a small part of it, see it from too far away, because there is insufficient light, or simply because the object is unfamiliar to us. In all these cases we are seeing without identification of form, or with only partial identification. By not identifying the object seen we see it afresh. Later we may decide it is "only" a stain on the ceiling or a shadow, at which point its mystery is dispelled and the form becomes ordinary. I try to capture a form without identifying it. This means capturing the form as pure form, uncontaminated by reference to subject matter. There can be surprising beauty in a ripple, reflection or glint of glass, and I believe that we perceive this beauty most clearly before we realise it is just a ripple, reflection or glint. Before identification takes place we see pure form rather than a familiar shape or shapes. The essence for me is that before you identify the subject in one of these semi-abstract images you see it with new eyes.

Perhaps the above rationale affords an insight into some of the motivation for creating abstract art. The artist is interested in shape not subject, in seeing things anew, without the history of past associations and reactions. They are interested in pure seeing, not in seeing identifiable forms.

“P1040267f Maroubra flow” by Tad Boniecki

Liberation from form

Abstract art is the negation of Goethe's profound observation that form liberates. With form absent, the 'liberation' is meaningless. It is meaningless because it leads nowhere except to the blank or randomly coloured canvas. From the lay viewer’s perspective this apparent liberation is of no value at all. Randomness (or apparent randomness) does not satisfy our esthetic needs. Neither does blankness. Human beings are pattern seeking and pattern creating animals. An image with no easily discernible shapes or patterns is frustrating to most of us. The other reason why most of us do not value random-looking images is that we think (rightly or wrongly) that any other random assembly of the same elements would be no better or worse than what, say Pollock, has produced. The other drawback to minimalist art is the “my five-year-old could do that” syndrome. It is hard for most of us to appreciate an image that is childishly simple or appears to be carelessly put together.

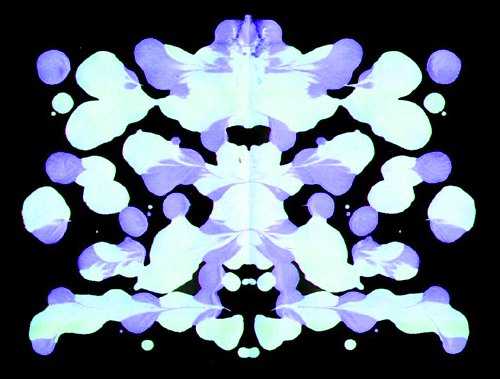

Rorschach test

Abstraction in painting is taken to its logical conclusion in the case of the square canvas that has been painted a uniform black. Perhaps the artist is saying to the viewer: "Read anything you like into this, just let your mind fantasise freely". A black canvas could be interpreted as depicting the negation of everything, or as containing the primeval void, or as a symbol of the end of creativity. It could be asking the viewer what they expect to see in an art gallery. There may be no "correct" interpretation, or all interpretations may be "correct"; but who cares? This is the essential stumbling block with abstract art: people do not wish to undergo a Rorschach test each time they see a painting. They do not know what was in the artist's mind and they do not care to make the effort to dredge up something from their own subconscious. Is the image below a work of art or a psychological test? (3 points)

Plate from Rorschach Test (modified so as not to infringe copyright)

The Rorschach approach to the appreciation of abstract art encounters at least three problems. Firstly, it requires time and effort on the viewer's part. If a hundred canvases are to be viewed in an hour, then how much interpretation can be generated for each piece? We view each one for about ten seconds and move on. The second problem is that most abstract art leaves one's mind deliciously blank. In the vast majority of cases it does not evoke long forgotten memories, travel to foreign parts, sexual daydreams, or hazy landscapes. The most serious problem, however, is that one is not satisfied with an interpretation that is manifestly arbitrary. I may think that "Blue Poles" is like meandering through a marsh while whistling Vivaldi, but I have little confidence that this interpretation is in any way relevant to what Pollock had in mind. Why bother to look for an interpretation if each one is as arbitrary as the next?

The abstract artist may counter with, "But I don't mind what you see in the canvas. So long as it elicits a response and makes you think of something. If you read in a message of any sort then I will be happy." The problem is that most often there is no response, apart from boredom, incomprehension, or even derision.

So the abstract artist requires a greater involvement from the viewer than does the figurative artist. They want the viewer to read in a feeling, a message or statement, perhaps a comment on art, society, or the high price of artists' materials.

Poetry vs prose

Another analogy is that of poetry and prose. Representational art is like prose: it is pretty much clear what is being said, or at the very least the subject of the piece is apparent. Abstract art is more like poetry, which requires the recipient to look for symbolism, hidden meanings and to see what is not visible. Perhaps abstract art is really about what the eye cannot see, just as poetry is about what prose cannot express.

Progress seen as the rejection of the old

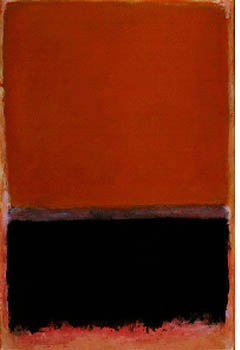

One way to see the development of modern art is as a progressive rejection of all previous conventions, methods and aims. It is a story of the rejection of rules and boundaries. Seen in this light, the blank canvas or a random assembly of dots are the logical culmination of the historical process. Such a culmination may be logical, but it looks like a dead end. The canvas below is more varied than some of Rothko’s other works – I thought it would be too boring to include an image that was nothing but a uniformly coloured rectangle.

“Untitled” by Mark Rothko

A little understanding is dangerous

Unfortunately the anarchic nature of modern art is not helpful to the would-be appreciator. The only thing they can be confident of is that whatever they think about a particular artwork, that thought is bound to be wrong. The abstract artist John Adams Griefen has some interesting thoughts on understanding art:

The problem, of course, is that one

cannot understand art, explain art, or say why it is good or bad. Let me

repeat: art cannot be "understood". Our familiarity with art can be

broadened and enhanced by art history and good writing on esthetics, but this

has nothing to do with and bears no relation to direct experience with the

work. Art must be experienced intuitively.

It must make one react, because without

reaction there is no experience.

When someone says "I don't

understand" he or she is either blocking the reaction or just not getting

it. People are not used to accepting a powerful intuitive experience per se,

but this is the only way to experience art. Esthetic intuition is the way we

experience art. It is not rational. It is direct and unedited and personal.

Many great works of art have content that can be political and social and have

great importance, but these are content, not experience.

When someone asks "Can you explain

it?" the answer is no. But just because something cannot be explained does

not mean that there is no esthetic value there.

When people try to

"understand" or "have art explained" there is room for a

kind of fraud that undermines what art really is there for and what it has for

us. If people believe that art can be explained to them they can be talked into

anything… You can use the very same arguments for a good work of art as for a

bad work of art. Find an exposition of a work you like and then apply it to a

similar work of the same origin that you don't like. The expositions are often

equally applicable.

Griefen’s contention, that abstract art cannot be understood but must simply be experienced, echoes what we know about humour and poetry. The explanation of a joke we don't initially understand does not necessarily make it funny - either it strikes us as funny or it doesn't. We may understand the joke but still not respond to it. Likewise, a poem full of oblique meanings and subtle nuances cannot be explained using plain English. If that were possible then the poem would have been written in plain and unambiguous English in the first place. The same is true of music – like art it can be analysed, but this is not the point of listening to it.

Yet Griefen is a little disingenuous. Although it is true that analysis and emotional response are two entirely different things, I am sure he would allow that analysis does enrich our experience by telling us what to focus on. Knowledge of what we are experiencing changes our experience in all fields, including in art. There are abstract paintings where the artist's intention is well known. In such cases this knowledge should be seen as relevant.

For one extra point: what would be the point of “understanding” the Arp painting shown below?

“Constellation with Five White Forms and Two Black, Variation III” by Jean Arp

Back to the blackboard

I thought that I might gain some clues to the appreciation of abstract paintings by looking at semi-abstract ones, given that there is a continuum of increasing degrees of abstraction, and that historically abstraction arose in a gradual manner. Unfortunately, I soon realised that I don’t know how to interpret semi-abstract works either, or even purely representational works, for that matter.

“The Mill” by Jacob Rembrandt

We can identify the content of representational art, such as in pictures by Dali, Rembrandt or Monet, but does that mean we understand this art or appreciate it? I think not. It merely gives us the comfortable feeling that we know what is going on, because we know what the painting is about. All we really lose when we move from figurative to abstract art is this surface level of “the painting is a depiction of xyz”. We only lose the story, and the story is not necessarily the meaning of the picture.

How do we expect to understand or appreciate any artwork from any period? There are many ways. A picture often tells a story or describes a scene – this is the basic literal level, like knowing the plot of a novel. What angle of view is it painted from and how is perspective used? We may see it as a thing of beauty or imagine how it would look in our home. We look at the use of colour and line, composition, contrast, shading, unity, variety and balance. The painting can be analysed much as a poem can, in terms of literary devices, symbolism, rhythm and so on. Then there is the mood of the piece. What has been selected for inclusion and what left out? What is being emphasised? The general topic of art appreciation is beyond the scope of this essay. Suffice to say that except for the first two elements listed above, all the others may be applied to abstract art as well as to figurative art.

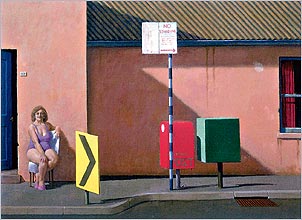

The problem of interpretation is not really any different with old-fashioned representational art from the problem with abstract art. The realistic depiction of the subject is only one aspect of conventional art, and this skill has been rendered unimportant by the invention of photography. Yet realistic representational art has continued long after photography became accessible to all. Clever painters such as Geoffrey Smart create deceptively realistic looking canvases, yet these images show us something new that we have not seen before.

“Cathedral

Street, Woolloomooloo” by Geoffrey Smart

I have the same problem appreciating a Rembrandt as I do with a pure abstraction. I may value the skill of the Flemish master, but does that mean I understand the work, or that I appreciate it at a level deeper than my response to a pleasant illustration in a magazine? A lot of so-called great art from centuries past leaves me completely unmoved. Just because it is a Rembrandt that doesn’t mean I find it beautiful.

Music

Interestingly, another abstract art - music - does not suffer from the problem of interpretation. No-one worries about the meaning or lack thereof in any piece of music, whether popular or classical. Vocal music and ballet are exceptions in that they rely on a text or story, but other music does not. Even so-called programme music, which describes a scene or tells a story (such as Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique) does not suffer any problems. The listener may or may not be able to read the story in the music, but it hardly matters. Either the music is satisfying to hear or it isn't. At most, the interpretation adds interest to the piece. It cannot render a good piece of music bad nor vice versa. Intellectual understanding is beside the point in music. The difference between music and painting, to the painter's eternal regret, is that music has a direct and emotional effect which painting cannot match.

Art as decoration

One approach is to see an abstract painting as a purely decorative object - you like the colours and form, or you don't. Yet this is missing the point. Art is not just about beauty. It is also about expression. With purely abstract art the communicative aspect does not come through very well, because there is no pre-existing language, as there is in figurative art, where recognisable shapes function as words or sentences. By contrast, the viewer is required to "read" an abstract work on the fly, without being able to draw on their normal visual vocabulary. To use a literary analogy, it’s as though they have to discover or identify the language in which the work is written before they can read or translate it.

What clinches the argument against the idea that abstract art is primarily decorative is the simple fact that most of it is not pretty or pleasing to the eye, and is not intended to be. Indeed, many modern artists actually disdain beauty.

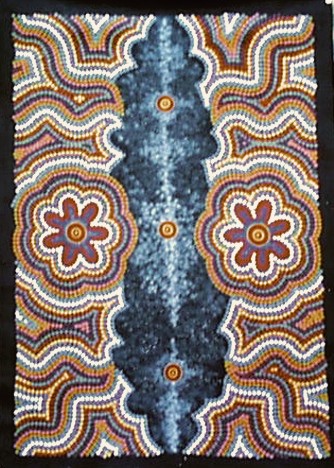

Aboriginal art is not the key

In the case of Australian aboriginal art (see below) one could say that there is a language known to the Aborigines, which they use to "read" their traditional paintings. It may be hard for outsiders to learn this language or for the Aborigines to articulate it, but I am sure it is something that they grow up with, just as we grow up with soft toys and model cars. So in a sense their art is not abstract in the way that modern art is. Put simply, their art is symbolic, not abstract. In the same way a circuit diagram ceases to be an abstraction the moment you realise its context and the meaning of the symbols.

“Milky Way” by Mary Dixon

A secret language?

A friend of mine wrote, “I often suspected that artists had a ‘secret' language for understanding modern art in the same way as the Aborigines do, but I just wasn't part of it.” I sometimes think this too. There probably is something of the kind, but it would be impossible to lay down its rules. No two people would ever agree on a common code. If despite this, a code were ever established then artists would immediately subvert it, since it would be another restrictive convention to overcome in the eternal quest for freedom.

It makes more sense to ask whether a particular abstract artist has their own symbolic language specific to them (I don't just mean their style). Apparently Dali used certain recurring symbols (such as beans, ants and struts), and these had well-defined meanings. Some artists may be willing to explain their personal symbolism, but it weakens a work of art if it cannot stand on its own because its appreciation relies on extraneous knowledge. It also begs the question of how much eloquent interpretation can be heaped upon any canvas whatsoever, even (or especially) a blank one.

In any case, I know that when I paint an abstract there is no symbolism involved, at least not on the conscious level. Of course one could argue that there is no such thing as abstraction without symbolism, if you take into account unconscious symbolism, but that argument can never be decided one way or the other.

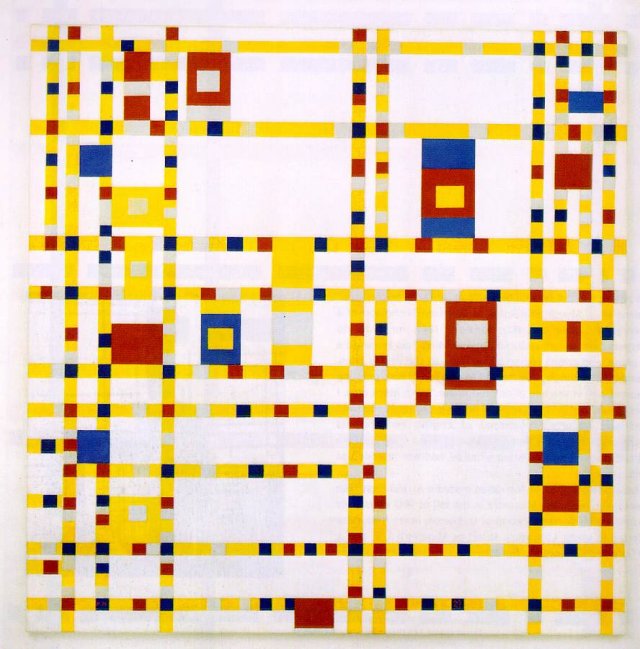

The Mondrian below is completely abstract, yet it is easy to identify a gridwork of streets seen from high above. So whether any particular work is truly "abstract" or not is always open to discussion.

“Broadway” by Piet Mondrian

What do artists want?

To appreciate abstract art we need to know what it is that the abstract artist wants to do. Here is Tao Ruspoli’s explanation:

With the gradual abandonment of

representation as its primary aim, painting went from being a copy of something

already existing to a construction of something entirely new. In Gombrich’s

words, "the modern artist wants to create things. The stress is on create and

on things. He wants to feel that he has made something which had no existence

before. Not just a copy of a real object, however skillful, not just a piece of

decoration, however clever, but something more relevant and lasting than

either..."

This explanation is both highly general and persuasive. Again, though, the problem is that it gives the puzzled viewer little insight into how to look at an abstract work. I am led to the conclusion that abstract art is simultaneously a powerful medium of expression for the artist and a very poor vehicle of communication with the viewer. This is another way of saying that it is extremely personal.

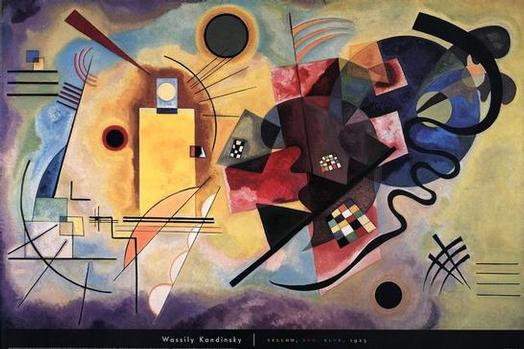

“Yellow, Red, Blue” by Wassily Kandinsky

Moving into a pure visual language

Here is what Robert Simpson wrote about his forays into abstract painting:

Some of this work had a "rightness" or was satisfying and complete without actually describing anything.

When I paint I often start with something tangible that we all can relate to, nature usually, but at some

point I become more interested in the voice of the paint, move into the pure language. I attempt to

achieve figuration without imagery, hoping that the residue has something worth looking at. Painters

working in an abstract style can develop a 'pure' language - akin to music - that in its purity can be

immensely satisfying. For example, Beethoven was somehow able to allude to the changing moods of nature

in his "Pastoral Symphony" by using a combination of notes, which is an abstract notion.

When you

look at a great abstract work by a great abstract painter, say De Kooning or Rothko, you become aware

of the sense of balance, harmony, what is emphatic, what is subdued, the spatial order, but also the

mystery, the searching that can take the receptive viewer beyond what we know into the "otherness" of

art that somehow can't be put into words. This strange "rightness" (for want of a better word) that the

painting is like nothing that we have seen before, yet it looks like it belongs here, should be here

and that the world is a richer place for it.

The power of abstraction

There are other explanations of what abstract artists set out to do, indeed every artist may have a different explanation. This is from abstract painter Harley Hahn:

With the coming of abstraction, artists

had, for the first time, a powerful tool that would allow them to bypass

literal perception and reach into this otherwise impenetrable world of

unconscious emotion. This was possible because, the more abstract a work of

art, the less preconceptions it evokes in the mind of the beholder. Kandinsky's

work is striking in its ability to bypass our consciousness and stir our inner

feelings.

One of the purposes of art is to allow

us indirect access to our inner psyche. Great art affords a way to get in touch

with the unconscious part of our existence, even if we don't realize what we

are doing. In this sense, the role of the artist is to create something that,

when viewed by an observer, evokes unconscious feelings and emotions.

The reason abstract art has the

potential to be so powerful is that it keeps the conscious distractions to a

minimum. When you look at, say, the apples and pears of Cézanne, your mental

energy mostly goes to processing the images: the fruit, the plate, the table,

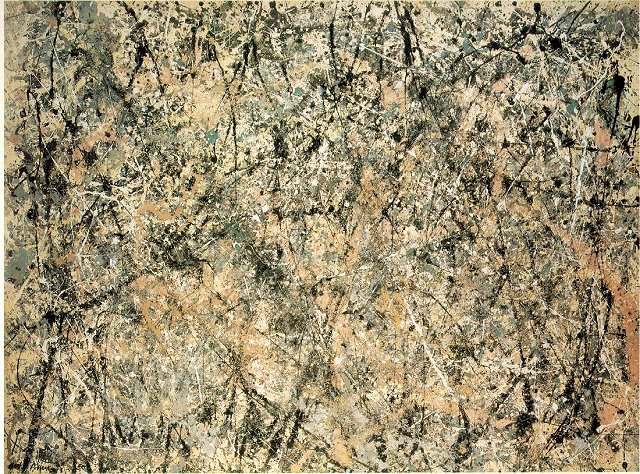

and the background. However, when you look at "Lavender Mist", you

are not distracted by meaningful images, so virtually all of your brain power

is devoted to feeling. You can open yourself, let in the energy and spirit of

the painting, and allow it to dance with your psyche.

Award yourself 5 points if you can rhumba with the grey fog below.

“Lavender Mist” by Jackson Pollock

Of the goals of his own painting, Hahn wrote: "that it is possible to invoke feelings in another person that are similar to the feelings you felt when you created the work." See how you go below: 10 points for a correct identification.

“Blue #1” by Harley Hahn

Hahn's views are thought-provoking and they again underscore the personal quality of abstract art. Yet they do nothing to solve the main problem for the viewer. When we stand in front of a canvas full of streaks and blotches, such as "Blue #1", this does not evoke any emotion. There is not enough to engage the eye and nothing to latch onto. Abstract art may give access to the depths of the psyche, but it does so for the artist, not for the beholder.

The abstract artist wishes to communicate with the viewer. With perhaps a few exceptions, they do not set out to puzzle or frustrate the recipient. Yet it seems to me that they have neglected to take the viewer with them, as every communicator needs to do.

A scientific approach

It would be interesting to run an experiment in which a number of abstract artists wrote down the feelings they were expressing in their canvases, ask some connoisseurs of abstract art to write down their responses, and then to compare the two. In the absence of such a controlled test, I speculate that the correlation would not be impressive. It may be that a canvas expressing fear would be registered as such by the sophisticated viewer, but I wonder how much more specific the communication could be. In any case the communication would only take place with a select few. Not many people are able to dance with abstract images.

“Still Life:

Flask, Glass, and Jug” by Paul Cezanne

Inverting Hahn's view

One could reverse Hahn’s contention by arguing that in the case of an abstract canvas we waste our mental energy on trying to make sense of its incomprehensible squiggles, rather than responding to the internal relationships or other qualities of the piece, unlike with a representational work. Because Cezanne’s fruit is familiar, we can more easily focus on his use of colour and on how he transforms an ordinary scene using his particular visual imagination.

The removal of all familiar elements from a painting may indeed clear away irrelevant distractions from the creative process for the artist. Yet it has the opposite effect for the lay viewer, as the absence of anything familiar is in itself a distraction from appreciating the work.

The annoying question, "What is it?" may be a futile one in the case of most abstract art. Yet we are forced to ask it when we face each new artwork, until we realise that there are no identifiable elements in the piece. We need to ask what is being represented because there are many semi-abstract paintings that appear entirely abstract until we examine them more closely and manage to discern familiar shapes. For instance the Miro shown earlier looks entirely abstract until one examines it closely. By contrast, the Matta below looks as though it might contain some familiar shapes, but doesn't (in my opinion).

“Morning on Earth” by Roberto Matta

Internal vs external reference points

Like fractal images, the scene above is not recognisable, yet it draws us into Matta’s private world. There is richness and complexity here, though these are comparatively rare in abstract art. An informal survey showed that out of 53 famous abstract canvases, each by a different artist, 37 were what I call “simple” or “geometrical”.

Richard Hooker points out that in non-abstract art there are two points of reference. There are the elements of the external world that are depicted in the piece, ie its subject, and the internal elements of the painting, such as lines, colours, contrasts and mass. So we come to terms with the piece on two levels, the external and the internal. With an abstract canvas there is no external reference, so it can only be understood in terms of the design elements of the painting itself, ie line, colour and so forth.

During the 20th century the design elements of a painting became more important than the requirement to depict the subject. Hooker parallels the development of abstraction in art with the gradual abandonment of tonality in music (completed by Schoenberg). Tonal music is based on a key signature that regulates what notes can be used in a particular piece and how the notes can be combined together. When you listen to a piece of tonal music you make sense of it in two ways. Firstly by (unconsciously) relating the sounds you hear to the key signature, and secondly you relate the sounds to each other, that is, to the internal design of the piece. Atonal music, on the other hand, has no key signature. If you listen to a piece of atonal music and relate it to a tonal scale then it will sound all wrong. This is as futile as asking “What is it?” of an abstract canvas. The only way to listen to an atonal piece is to listen to the relationship of each note to the other notes. Hooker concludes that, as in abstract art, an external standard has been removed and all that is left for our understanding to work on are the internal relationships of the music.

Question: is atonal music written for tone-deaf people? Award yourself one point for no, and one point for yes.

Parallels with music and literature

Modern art music (definition of 'modern': music that will seem old-fashioned in fifty years' time) features some hard-to-listen-to composers. Dissonance and arbitrary sound patterns have taken the place of harmony and melody with many a composer since Schoenberg. Much of this music is only of interest to critics, theoreticians and other composers. It is not designed to please the human ear. On the other hand, there are difficult composers, such as Olivier Messiaen, whose music does not lack inspiration, and who repay the careful listener. It would be easy to dismiss Messiaen as indigestible if one did not make a sufficient effort. It took me a while to appreciate his works. We need to allow time to appreciate abstract visual art as well. Griefen suggests that the only remedy for "not getting" a piece of modern art is to look again.

One of the most vaunted of all twentieth century novels is "Finnegans Wake". It may be true that this is a profound work and that its means of expression are masterly, but the simple fact remains that if a book is an act of communication then this novel by Joyce fails dismally with 99% of people. It is not intelligible because Joyce has created his own private language.

Paul Rosenfeld suggested that "the writing is not so much about something as it is that something itself... in Finnegans Wake the style, the essential qualities and movement of the words, their rhythmic and melodic sequences, and the emotional color of the page are the main representatives of the author's thought and feeling. The accepted significations of the words are secondary." This is reminiscent of the notion that abstract art is not a representation of something but the object itself. In other words, Joyce has transformed the novel from an act of communication into an act of expression.

A similar situation holds with abstract art. Perhaps "Blue Poles" is a masterpiece (and perhaps not) but to the vast majority of people it is an expensive joke. In fairness to Pollock, it should be pointed out that his canvases are huge, allowing the viewer almost an experience of immersion. Viewing the small reproduction below can only hint at the experience of standing before the painting itself.

"Blue Poles" by Jackson Pollock

So what is abstract art?

A friend of mine commented on an early draft of this piece, "You haven't really said what abstract art is all about." I doubt that there is "an answer". There are many partial answers, some of which are mentioned above. I thought of listing what I have read about specific artists, but that would be a jumble of so many fragments. Some artists are just interested in playing with light, manipulating colour, achieving a particular effect (such as the impression of motion), or in creating illusions. Others deal, or profess to deal, in emotions. Or they want to express the effect a scene had on them, rather than painting the scene itself. Still others want to push a political or social message. Others are only interested in esthetics, ie they want to produce an image that pleases them in some way. Certain artists write manifestos - these exist for probably every one of the many art movements of the 20th century. Other artists are not articulate, or refuse to put things down in words, insisting that their works must stand on their own. It is tempting to think that abstract art means something different to every abstract artist.

The gap

Essentially, there is a large gap between the abstract artist and the general public. It was created some ninety years ago and it persists. The gap can be seen as a strong divergence of opinion regarding what is or isn't art. Arguably there is an "emperor's new clothes" process going on, in that a lot of people swallow their doubts and assume that our cultural arbiters know what they are doing - if it's in a gallery it must be art. But what is art? That's a 64 dollar question. These days an "artist" can do (or not do) anything they like, pick up a bit of gravel or whatever, put it in a glass case and exhibit it as art. It is hard to know where to draw the line. People stand in front of the air conditioning duct in the gallery and wonder whether it is an artwork. (Is it? - 2 points). My position is to let them call 'art' what they will, but not to expect me to show it respect just because it is in a gallery or museum. Perhaps it is better to ask: "Is it good art?" That has to be decided on an individual basis. If the so-called artwork connects with some viewers then it has some value. If everyone except the author thinks it is just a bit of gravel in a glass case, then it has little or no value (beyond the market price of the gravel). When Marcel Duchamp exhibited an urinal as an artwork in 1917 he was breaking new ground and making a point about how we tell art from non-art. He was saying that art is whatever you say it is. Ninety-four years later there is little sense in other artists repeating his gesture, as they still do. The same applies to the blank canvas. Whatever may have been its historical value as an artistic statement, there is no point in repeating it.

Duchamp's urinal

Ahead of our time?

On the other hand, another of my friends observed that, in so far as artists are visionaries, they "are opening the doors to some unknown world or language which I am yet to discover". Art history features numerous artists whom we now consider important and whose works we moderns find accessible, but who were not understood during their lifetimes. What we now call great art was usually ahead of its time. When a critic complained to Beethoven that he couldn't understand one of his late string quartets, the composer replied, "They were not written for you but for the future." The last Beethoven quartets are rightly counted among his masterpieces.

By way of a conclusion

The main problem with appreciating abstract art is that whereas people want to connect with it in some way, the lack of anything familiar prevents this. Because there are no rules and no language for reading such art, the viewer is left in a vacuum. Interpretations all seem arbitrary and hence do not satisfy. An alternative is to evaluate the abstract artwork as either an esthetic product or else as an image that may be valued for being intriguing, striking, powerful, or even moving.

Ultimately, no guidelines can be given. The viewer needs to develop and then trust their intuitive reaction to the artwork. The experience of abstract art is highly personal, both for its originator and for the recipient. Abstract art is simultaneously a powerful medium of expression for the artist and a singularly poor vehicle of communication with the viewer.

Tad Boniecki

May 2004

Updated September 2011

PS If you scored between 1 and 100 points then you are a reasonably proficient art critic, if you got over 100 then you cheated.