Coined in 1999 by then-Cornell psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, the eponymous Dunning-Kruger Effect is a cognitive bias whereby people who are incompetent at something are unable to recognize their own incompetence.

The irony of the Dunning-Kruger Effect is that, Professor Dunning notes, "the knowledge and intelligence that are required to be good at a task are often the same qualities needed to recognize that one is not good at that task - and if one lacks such knowledge and intelligence, one remains ignorant that one is not good at that task." Across four studies, Professor Dunning and his team administered tests of humour, grammar, and logic. They found that participants scoring in the bottom quartile grossly overestimated their test performance and ability. The combination of poor self-awareness and low cognitive ability leads them to overestimate their own capabilities.

Dunning and his colleagues have also performed experiments in which they ask respondents if they are familiar with a variety of terms related to subjects including politics, biology, physics, and geography. Along with genuine subject-relevant concepts, they interjected completely made-up terms. In one such study, approximately 90 percent of respondents claimed that they had at least some knowledge of the made-up terms. Consistent with other findings related to the Dunning-Kruger effect, the more familiar participants claimed that they were with a topic, the more likely they were to also claim they were familiar with the meaningless terms. As Dunning has suggested, the very trouble with ignorance is that it can feel just like expertise. Ignorance is like alcohol, giving us unwarranted confidence in our abilities.

People with less than average abilities tend to overestimate their true abilities, while those with higher than average abilities tend to not realize how much better they are than the average. That is, some people are too ignorant to know how ignorant they are, while competent people assume that what is easy for them is also easy for most people. Dunning and Kruger claimed that the "miscalibration of the incompetent stems from an error about the self, whereas the miscalibration of the highly competent stems from an error about others."

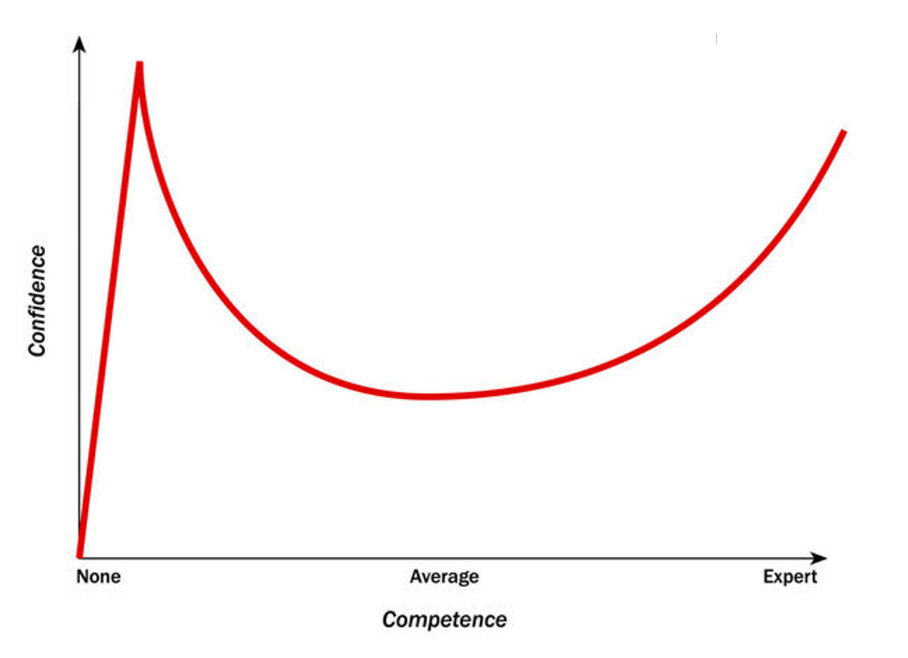

At the bottom left of the graph, competence in a given subject is zero, as is confidence. However, as a person learns a bit of the subject, confidence grows substantially. As a person continues to grasp the basics, their confidence reaches a maximum, as they believe themselves to be among the few who understand the subject. This peak is often referred to as Mount Stupid. As a person learns more about a subject, they begin to see how complicated and involved it really is. As seen in the graph, confidence dips sharply. As competence increases confidence bottoms out. Fortunately, though, confidence begins to grow again and a person climbs up the slope as they gain mastery of a subject.

Examples of the Dunning-Kruger Effect abound. One study of high-tech firms discovered that 37% of software engineers rated their skills as being in the top 5% of their companies. Drivers consistently rate themselves above average. This is probably because we rarely get objective feedback on our driving, unless we cause an accident. In a classic study of faculty at the University of Nebraska, 68% rated themselves in the top 25% for teaching ability, and more than 90% rated themselves above average.

Those with the loudest voices often have the most confidence but little competence. The less they know, the less they are aware how much more there is to learn. Trump is an extreme example. The Dunning-Kruger Effect explains the spread of conspiracy theories and nonsensical ideas, such as that 5G is the cause of the pandemic. People with no scientific training spread misinformation thinking they are in the know. By contrast, those with real knowledge realise how much they don't know, so they tend to be silent.

Knowledge is like an island: the more knowledge, the greater the shore of the unknown. The converse is that if you know very little about a topic then you cannot be aware of its depths.

A real threat to our society is the apparently growing anti-science movement, which is fueled by the Dunning-Kruger effect. Those on Mount Stupid have disproportionate influence, often supporting anti-science candidates, intentionally or unintentionally spreading misinformation, or even helping to create anti-science legislation. In general, society suffers because politicians are called upon to make wide ranging decisions even though they may lack any expertise in the related areas.

It is hard for most people to admit they are wrong. It seems we are all vulnerable to the Dunning-Kruger effect. Even if we try to take it into consideration, we are likely to over- or under-compensate. To escape the Dunning-Kruger effect we need to develop metacognition, the ability to see ourselves objectively, at least to some degree. Perhaps the only way to do this is to repeatedly submit our competence to objective tests.

A friend asked me where I think I am on the Dunning-Kruger curve. This is a very tricky question. To place myself on the graph requires a splitting of consciousness. I have an idea of where I am in each domain in terms of my confidence in it. That part is not hard. The hard part is to attempt an objective assessment, as a neutral outside observer might make. This is problematic - in my view impossible. If a domain had a test that I could undergo to measure my competence, analogous to an IQ test, then I could do the test and see whether I did better or worse than I expected. In the absence of such a test, all I can do is give my own assessment of my level of confidence in any given domain, and leave its accuracy as an open question.

I cannot place myself on the graph, because that requires an objective view, which obviously I cannot have of myself. I could only place myself on the graph if I knew my confidence AND also knew my actual level of knowledge. However, there is a feedback mechanism, because if I discovered that my actual competence were much lower than I expected then, of course, my confidence would drop, as it does when I fail an exam.

Why do we tend to over-estimate our knowledge and skills? An obvious answer is narcissism. No-one wants to see themselves as ignorant or unskilled, let alone incompetent. Yet seen objectively, all of us are ignorant of about 99.99% of current human knowledge and few of us are highly skilled in more than a handful of the hundreds of areas of expertise that humanity has developed over millennia. Of course, we have ways of making our ignorance palatable. We tell ourselves it is enough to know a broad outline of a subject like quantum physics or stem cell research. It helps to dismiss entire fields of knowledge as being of little importance or relevance to us, eg ancient Chinese history, the study of unicellular organisms, theology or depth psychology. By means of these strategies we make ourselves feel reasonably knowledgeable and competent and hence take our rightful place on the Dunning-Kruger graph!

Of course, now that we all have access to AI, wikipedia and other sources of instant knowledge, we tend to outsource expertise. We do not bother to do the hard work of assimilating knowledge and expertise within our craniums because it is already out there in the virtual realm.

Self-assessments by famous people are notoriously inaccurate. Freud believed he had a second-rate mind. Isaac Newton, "I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me." Bach, "I worked hard. Anyone who works as hard as I did can achieve the same results." Einstein, "I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious."

Forcades, commenting on Nadal's success, reveals the profound value of humility, "Humility is the recognition of your limitations, and it is from this understanding, and this understanding alone, that the drive comes to work hard at overcoming them."

Written in July 2020, updated in April 2025