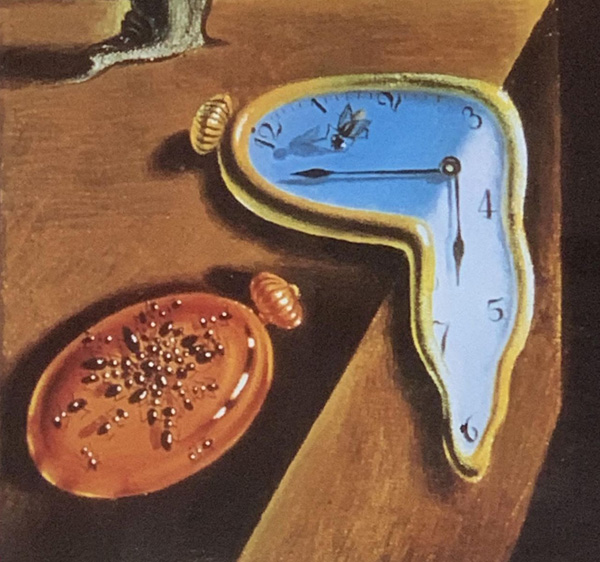

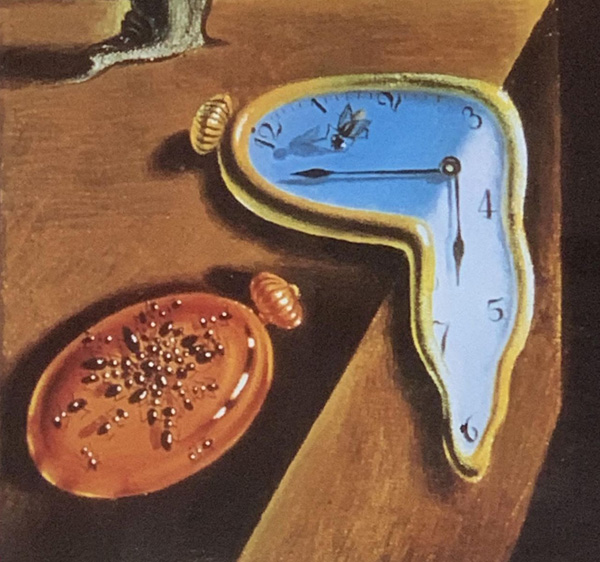

Why does Christmas come faster each year?

The speed of time depends on which side of the toilet door you are on.

The speed of time depends on which side of the toilet door you are on.

Objective vs subjective time

From the viewpoint of classical physics, it makes no sense to say that time speeds up. Time is the measure of all speeds, but does not itself have a speed. Of course, Relativity Theory fells us that the rate of passage of time does alter when we approach the speed of light, and even at lower speeds. However, the effect is normally so tiny as to be inconsequential for all human purposes.

So much for physics. As conscious beings we experience something that has no meaning in physics, namely flowing time, ie our awareness continuously passing from one moment to the next. Since the notion of flowing time has no physical meaning, we can assume that it is subjective, and hence varies due to mental or other causes.

A paradox

The subjective speed of time as we perceive it has two quite separate and contrasting dimensions. One is the perception of time passing in the present, and the other is the perception of the passage of time as we look back in our memory. This is an important difference, as shown by the paradox that old people say, "The hours drag, but the months fly by."

If our life is mainly routine then time drags in the present, ie we are bored. On the other hand, routines do little to lay down memories, so that our week seems empty of incident as we look back on it. Hence it seems that a week has passed with hardly anything happening, giving us the perception that time has flown by.

Looking back on a week is different to living through it. As we look back on a week in which nothing seemed to happen except routine, it appears empty. Memory has the function of summarising our experiences. So if little is going on then our memory tells us that nothing in particular happened. The week does not register and hence time is perceived as having flowed quickly. It is next week before we realise it. Yet during that week time may have flowed slowly for us as we navigated our familiar routines. So perception of time's flow has an at-the-time and an after-the-fact component and these two are likely to contradict each other. The paradox is that time slows down as it is currently perceived but speeds up as it is remembered.

Sensory deprivation experiments demonstrate a disruption of the sense of time. Lyall Watson writes that the most noticeable psychological effect of sensory deprivation is the slowing down of time. A routine is like a mild form of sensory deprivation, as we operate on autopilot.

Boredom vs stimulation

As illustrated by the toilet door joke, our thoughts and feelings influence our perception of the passage of time in the present. Basically, the at-the-time perception of the speed of time is a measure of how stimulated or bored we are. Being in a hurry, rushing to get things done speeds up the perceived rate of time in the present. By contrast, if we have nothing to do then time drags. If we are in pain, in acute physical discomfort or have an over-full bladder then time can move with agonising slowness. The same is true if we are stuck in a protracted traffic jam.

Being mired in stationary traffic, while already late for an appointment illustrates the difficulty of analysing time perception. Paradoxically, our at-the-time speed has two contradictory rates. On the one hand, time is dragging painfully, as we inch forward. On the other, the minutes tick by quickly, as we accumulate yet more lateness. This is because we are simultaneously stimulated by our pressing hurry and bored by the traffic jam.

Time is only perceptible as change, so the fewer changes we experience, the less we perceive the flow of time. If we are sitting at a lonely bus stop for an hour, with no people or cars appearing, then time in the present will probably drag. If on the other hand, we spend an hour with an interesting friend at a busy cafe then time will move fast, especially if we are obliged to go back to work!

Breaking up our habits has the power to change how we perceive time. To slow down remembered time we need to be unpredictable, vary our routines, do new things. Doing something creative is an excellent remedy.

Time speeding up in the present

There are a heap of modern distractions, especially mobiles, which prevent us from getting things done, causing time in the present to pass quickly. In addition, the multiplicity of possibilities, of the things we think of doing, has the effect that there is always little time, and hence that time is passing quickly. A long todo list or a bulging schedule cause us to think we are short of time, ie that time is moving too quickly for comfort. A related factor is that we get over-ambitious, hoping to complete more tasks, or to do them in less time than is needed. This generates the feeling that time is running away from us or is speeding up. Likewise, if we are running late, time speeds up for us. The FOMO (fear of missing out) syndrome has a similar effect.

Time in the present can even stop

At the other end of the experiential scale, is the experience of being in flow, when we become one with what we are doing. This causes us to lose all sense of time in the present, while later increasing its remembered speed greatly. My partner observed that when she is absorbed in jewellery-making and is no longer an observer then time stops for her. She forgets to eat lunch.

Time is perceived differently by children

A child gets bored very easily, so waiting for half an hour seems an inordinate time to it. Observing little children, I get the impression that they cannot be satisfied for more than ten seconds or so. They need constant stimulation. Shallis writes that in the present, time seems to pass about 10 times more slowly for a six-year-old than for a 60-year-old.

On the other hand, the child always has new things to learn and experience. Every year, its life changes appreciably, just like its developing body. The multitude of new impressions causes the remembered year to be longer for them than for adults.

Measuring time's speed

How do we measure the subjective rate of time's flow as assessed by memory? We look at the clock or check the date, and then compare this with what we believed to be the hour or day. If it is later, then we say time has speeded up for us, and if earlier, then it has slowed. The problem with this judgement is that we compensate. When I am at my yoga class, I expect time to drag and I mentally compensate for this. By contrast, if I get involved in playing speed chess, I know that time will run away from me, and I try to compensate for this too.

When we sleep, we lose track of time, as there is no continuity of consciousness. This is especially so after flying in to Europe. We may awake having no idea how long we have slept, or whether it is day or night. We look out the window and consult the watch to re-calibrate our sense of time.

If my estimate of how much time has elapsed is correct, that means that remembered time has moved at a medium pace, neither fast nor slow. The objective measure of how much time has passed is the yardstick that tells me time, as I remember it, has gone fast or slowly.

Why Christmas arrives early

Because much less seems to fit into the day than when I was young, I now have a sense of impoverishment. Of not getting enough out of the day. As adults we find that time as measured by our memories moves ever faster. Many people say that Christmas arrives faster this year than it did the year before. Older people say this more than the young. However, young people also say the same thing often, which is curious. It could be that contemporary life, with its characteristic busyness, distracts us from important things. Because things we need to do remain outstanding, we have the impression that time is flying by. Here are some reasons for Christmas coming around August for us adults:

1) The older we are the fewer new experiences we likely have. Hence there is less to remember of what happened in a year or a month. Too much becomes routine. We have fewer new experiences than when we are young, so there is less to remember and so it seems as though not much has happened, though it is already October. We have experienced so many summers that another one seems like just more of the same.

2) The more familiar the world becomes, the less information our brain writes down, and the more quickly time seems to pass.

3) As we get older we become increasingly aware that our time is running out. The perceived and dwindling finiteness of what's left makes us bemoan time's speed. By contrast, children believe they are immortal and think nothing of wasting time.

4) We get over-ambitious, cf the mid-life crisis. There is so much we could be doing.

5) As our memories become less retentive we remember less, and so we have the feeling less has happened.

Another example is that of other people's kids. You hear about their birth and the next thing is they are finishing high school.

Time slowing down in memory

Looking back we assess the passage of time by means of the memories that we retain. So when a lot of things happen during a week we have the perception that much time has passed, yet only a week has elapsed. Hence we are surprised it is only Wednesday. This is the opposite of the week flying by without a trace. The more detailed the memory, the longer the moment seems to last. Time slows down when there is a drastic change in our life. If we are travelling to a new city every day then time slows down in our memory because so much has happened in a week.

Synchronising present with in-memory speed

Although I have drawn a sharp distinction between at-the-time vs the in-memory perception of time's flow, at some point the two start to coalesce. An example is playing speed chess, where we constantly refer to the ticking clock. The same is true of any activity where we time things to the nearest minute or second. In such cases, because we constantly recalibrate our notion of the passage of time, our perception of time's flow is closely aligned to the objective passage of time. Yet in spite of being in sync with the clock, we still may have the subjective feeling in the present that time is flowing rapidly. This would be felt especially if we are racing against the clock. If we are looking back on a short time interval, such as five minutes, then again the two perceptions of speed are likely to be aligned.

The speed of time's flow as we perceive it is a fuzzy thing. What can muddy the waters is that the two perceptions - present flow and remembered flow - can interact. In particular, their usually contradictory speeds can be reconciled by comparing our remembered speed with what we recall of how the flow felt at the time.

Looking deeper

Our twin notions of the speed of time, the ones I call at-the-time and the after-the-fact, are just a part of something bigger. This is our subjective, complex, paradoxical and fuzzy relationship to that thing we call time, which is arguably not a 'thing' at all. This relationship is composed of feelings such as "I am rushed" and thoughts such as "It is one o'clock". Such a mix of feelings and thoughts melds our subjective experience with objective time-keeping. This uneasy mixture produces paradoxes such as "the hours drag, but the weeks fly by" and "Christmas arrives faster each year".

Our relationship to time is moulded by our culture, a culture that values speed and efficiency and is fixated on schedules and timings. What about the aboriginal view of time? It is without doubt a very different animal. By looking at how other cultures conceive time we can discover that time is not the monster we moderns have created. Our culture trains us not to live in the moment, but to focus on schedules and to live a goal-oriented, ie a future-oriented life. As a result, we often feel the stress of time-pressure and the anxiety of juggling multiple tasks. That is why mindfulness and the approach of Eastern philosophies is a valuable counter-balance.

Time is like money in that it is difficult to hold it in perspective. We need to avoid the twin pitfalls of time-wasting and procrastination on the one hand, and of being on a task treadmill and stingy with our time on the other. Like money, time involves our emotions, as it holds out so many possibilities, only some of which can be realised. We often think, "If only I had the time to do this!" Yet this may well be a case of self-deception.

Conclusion

It is important to stress that we do not experience time at all. What we experience is change, whereas time is an abstraction we have created in order to understand change, and in particular, its speed. Time as conceived by the physicists is a poor fit for our experience of change. Our subjective world of perception, feeling and thought is linked to and depends on the objective world, but the two are imperfectly synchronised. Our varying perception of the speed of the flow of time cannot be reconciled with the mathematical view of time.

Although seen objectively, time does not vary, our subjective experience of time's flow is another matter. We feel it slowing down or speeding up and this feeling is as real as any other feeling, even though seen scientifically it appears illusory. Time has two different speeds for us, the speed we perceive now, and the speed we judge it to have based on our memories. Typically, when one of these is slow the other is fast, which appears paradoxical. The paradox is explained by the level of stimulation in the present and the density of memories looking back on the past. These two tend to be inversely proportional.